We can’t ignore mental health in retirement any longer

3 June 2019 By Victoria Tomlinson

To anyone working full time, retirement looks like a world of glamour and fun with stories of world-wide travel, walking the Pennines and endless coffees and lunches with friends.

The reality is that retirement has been named as the tenth most stressful event in people’s lives and dramatically increases the chances of both mental and physical health problems.

Everyone knows we are living longer, yet we have not yet adapted government social and health policies, nor properly involved employers in how best to help employees – nor looked at the generation of people who are retiring as one of the biggest opportunities for our economy.

The issue we see at Next-Up is that travel and coffees sound great for retirement – but the reality is they don’t replace the sense of purpose and fulfilment that work provides for so many. Being busy is not the same as feeling good. As one person said, “I have filled my diary and I am busy. Very busy. But my life is empty.”

Yet advice to doctors in the NHS Guide on Mental Health in Older People fails to recognise retirement as an issue or possible root of mental health. The guide does say to look out for bereavement as a likely cause, but does not mention the bereavement suffered when people leave work.

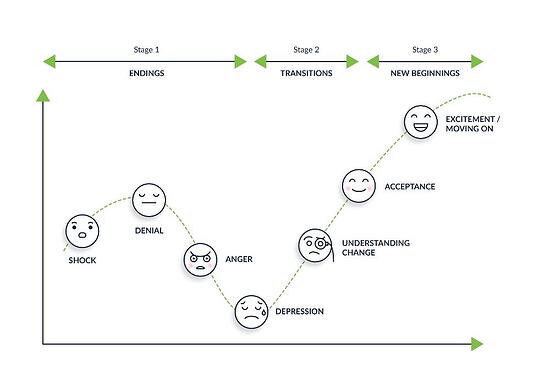

We have helped dozens of people who have retired and many are completely lost as to what they do next. And two things really strike home. The first is this issue of grief/depression. We use the Kübler-Ross grief curve to explain what emotions they may be going through. Almost without fail, people go, “Oh my goodness, I thought it was just me. That makes sense now. This is so helpful to understand why I feel so rubbish.” One man, who you would have thought was fairly happy with life, looked at the curve and said, “Oh, I am at the bottom of the curve.” In other words, he was depressed.

Kübler-Ross change curve applies to retirement as well as bereavement

When you think about it, retirement is a form of bereavement – overnight you lose your identity, status, network of colleagues and structure to your life. And for many, you lose your sense of purpose, a key ingredient for happiness and good health.

- “I thought that I was ready to retire mentally – but found that it actually took me three years to adjust – I grieved for my job and that process took that long. There was no help or recognition about the grieving process. I had to work through that myself and it was only after I came out the other end that I realised what had happened to me” (The Psychology of Retirement)

- “I absolutely hate it. I find it financially challenging, lonely and boring. I feel as though I am brain dead and I am being left further and further behind in learning new technologies and discovering new interests….. I find I am sinking into apathy and the less I do the less I want to do” (The Psychology of Retirement)

The second, perhaps biggest issue, is that people don’t know how to find purpose in their life. And it’s much harder than I think most people realise.

In this blog, I want to share the research around mental health and retirement and look at what can be done to minimise the risks.

Research on mental health and retirement

The research on mental health later in life tends to look at ‘older people’ – generally classified as aged either 55 or 60 plus – though some specifically reference ‘retirement’.

The challenge is that this generation of people spans 50+ years from say, a 55 year old retiring in pretty good health and running marathons up to the ‘elderly’ who could be in their late 90s, may be frail, with decreased mobility and suffering a number of chronic illnesses. All the research recognises that people may retire because of ill-health, and that people tend to get more illnesses as they get older anyway. However, some of the researchers have had a reasonable stab at comparing people of the same age still working with those not working and drawing what look like fair conclusions as to the impact of retirement itself – as opposed to ageing. I have included links to all of this so you can examine these findings in more detail.

Here is a snapshot from the research on mental health in retirement

- Depression is the most common mental disorder in older people. The symptoms can be distinctly different from depression in young adults and is often missed. The risk factors for depression include physical health problems, female gender, loneliness, life events (particularly bereavement) and loss of independence (NHS England)

- It is estimated that depression affects 22% of menand 28% of women aged 65 or over and 40% of older people in care homes (Age UK, 2016)

- About one fifth of all suicides happen in older people. The most common method is overdose. Suicide attempts should be taken seriously – a higher proportion compared to younger people are genuine attempts to die. Risk factors include being male, widowed, increasing age, social isolation, physical illness (present in up to 80% of cases), pain, alcohol misuse and depressive illness – past or present (NHS England)

- Alternatives to drugs are listed in the NHS England report as day centre attendance, befriending, help to attend religious ceremonies and healthy living or independent living programmes. (My personal view here is that people should be helped to find purpose, volunteer, become involved in their communities, help others – these days with technology, people can do all these from a bed or chair if they are struggling physically. While there are many who suffer from clinical depression, for the many affected by the process of retirement the issue is more about mindset and creating new purpose)

- Loss of work-related stress may be a great relief and good for health, but losing the daily structure and work relationships can also be stressful and harmful to health. Retirement is ranked 10th on the list of life’s most stressful events…… At least one study has shown that people who retired at age 55 had almost twice the risk of death compared to people who retired at age 60. The link between early retirement and early death was greater for men than women; men who retired at 55 had an 80% greater increase risk than women who retired at 55….. The most commonly researched marker of mental health in retirement is depression while another approach is to determine how individuals adjust to retirement and how satisfied they are with this life transition … There is increasing evidence that depression is associated with increased risk of retirement (The Psychology of Retirement)

- There are five key issues that can have an impact on the mental wellbeing of older people: discrimination; participation in meaningful activities; relationships; physical health; poverty…. If work or career is a major part of your life, consider how to deal with the changes to: the social aspect of your life if your job also provided friendships; your sense of self-worth and self-esteem if you felt valued at work; your financial security. If you haven’t had many interests outside of work it can be hard to ‘find something new to do’ and it may take a few attempts before you find something that’s right for you. Take your time and think about the skills you possess that can be put to good use and give you fulfilment – perhaps try helping out with a local community organisation or doing conservation work… You should also look to develop new friendships with people of all ages. Friendships with both older and younger people help to keep you in touch with the world as it changes (Mental Health Foundation – How to look after your health in later life)

- There are lots of reasons why your mental wellbeing can change. There may be a trigger point, usually a significant or distressing event, such as: retirement; bereavement; relationship or family problems; money worries; disability or poor health, including sight and hearing loss; being a carer; being on your own; the time of year…… What can you do to improve your mental wellbeing? Eat and drink sensibly; keep active; stay in touch and meet people; create structure to your day and set yourself goals (Age UK)

How to reduce risks of mental health in retirement?

The World Health Organisation’s report on Mental Health of Older Adults lists six priorities to ‘meet the needs of older populations’ – but I think is missing two really key points for the younger group of ‘older adults’. Here is their list

- providing security and freedom

- adequate housing through supportive housing policy

- social support for older people and their caregivers;

- health and social programmes targeted at vulnerable groups such as those who live alone and rural populations or who suffer from a chronic or relapsing mental or physical illness;

- programmes to prevent and deal with elder abuse; and community development programmes

For me, the missing points are

- helping people find purpose in their lives

- using their skills and experience to help others

Finding purpose is directly linked to good health – and lots of reports talk about its importance. But I have yet to find anyone who says how to go about this. I have been surprised at just how hard people find this, but when people’s lives have been wrapped up in work and family they haven’t had time to think beyond this and work out what they really care about, what matters to them. This is a topic I am looking at in a lot of detail and would welcome views and insights.

For the 50 to 70 year-old generation, we need a new approach – from employers, government, academics, social and health providers. These are how we see those priorities

- Segment the ‘retired’ sector, for health and economic policies. There are nearly 20 million people aged over 55; 12 million of these are over 65. Compare this to the 15.5 million under 19. The opportunities and needs of this older market are very different in a possible 40 or 50 year life span. Yet all the research tends to lump people together. You wouldn’t compare the needs of babies with teenagers in the same way – but that is just a ten-year span. We need to rethink how we look at this older generation and the help they need in the first few years as they retire

- Help people recognise their skills and use them in new ways in retirement. When people retire, they lose confidence very quickly – it doesn’t matter if you have been a dinner lady in a primary school or the chief executive of a FTSE – the issues are surprisingly similar. Yet everyone has so much to offer – whether mentoring the younger generation, volunteering, starting new projects or using their experience. This is an issue for private, public and voluntary sectors to work together and rethink much of the support offered, but also how they could use the experience of this generation

- Employers and pension providers to rethink and reshape their retirement planning offering. Most large employers and most major pension providers are offering pre-retirement workshops at anything between five years before retirement up to the final pre-retirement year. Feedback from people who go on these is that they are already variable in quality and engagement – a few have been labelled ‘dire’. This would be a chance to refresh and engage people in the workshops and include sessions on the realities of retirement and how to find purpose for what could be another 50 years of their lives

- Academics need to carry out research on the ‘retired’ or ‘55+ generation’ to nuance varying lifestyles. In particular, there is almost nothing around (that we have found) that looks at the particular issues of coming up to retirement and the three to five years after retirement. In our experience these are the critical years when the scene can be set for long term mental health problems – but get this new stage of people’s lives right and they can be the happiest they have ever been in their lives. We need to stop lumping everyone aged over 55 or 60 together

I believe the generation of people retiring now and in the next few years is one of the greatest untapped resources this country has ever seen. The challenge is how we ensure the potential cost of mental health problems is turned around to be an asset that benefits individuals, companies and the country.